The music of Mary Jane Leach on this album draws on several sources of inspiration. The first is early music, with its polyphony and modal harmonies. Modal writing, as adapted to twentieth-century thought, focuses on the prolongation of a fixed collection of notes, arranged into either a traditional or an invented scale. Melodies and harmonies are created freely from this collection, without forcing them into highly directional and strongly articulated phrases. The result is a luxurious stasis, with poles of attraction-pitches that serve as points of repose-strongly stated. From modal antecedents, Leach dervices her own unexpected twists and innovations.

|

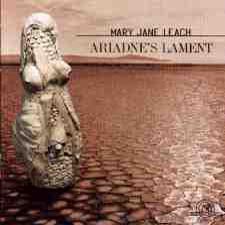

The influence of early music is evident in other ways. Like those of the Renaissance, Leach's scores are free of dynamic and expressive markings. Two of the pieces draw their musical material directly from Renaissance works: Ariadne's Lament from Monteverdi, and Tricky Pan from the fourteenth-century poet and composer Solage. The languages Leach sets-early Italian and French, ancient Greek and Cretan-also evoke a sense of connection to a remote past.

In her early compositional work, Leach experimented with recording individual lines on 8-track tape and then accompanying herself. This enabled her to be musically self-sufficient, and also allowed for more intricate textures than she could create with a single-line instrument. Tricky Pan, for solo countertenor and tape, is modeled directly on this technique. Gradually, as her music began to be more widely sought after by ensembles, Leach's fascination with multiple tracks led her to adapt it to live players: The choral pieces on this album all divide the chorus into eight independent parts.

While there is a substantial body of twentieth-century music that delights in the chimerical and the quickly transformed, Leach's music is from the esthetic which favors prolongation, resonance, long statements of subtly varied persistence. In that sense, her music is both easy to follow and mellifluously unpredictable. She has a careful ear for pacing and structural unfolding, often building her pieces to ardent, expressive arrivals. The traditional distinction between consonance, as pillars of stability, and dissonance-unstable moments that must inevitably seek out resolution-is maintained, though she will allow dissonances to flower and persist in ways her predecessors did not.

For many years, Leach has been involved in an ongoing project that focuses on the myth of Ariadne: Four of the works on this album, the earlier Ariadne's Lament and Song of Sorrows and the more recent O Magna Vasti Creta and Call of the Dance, are part of this project. In the classic telling of the myth, Ariadne falls in love with Theseus, and helps to rescue him from her half-brother, the Minotaur: But, after killing the Minotaur and fleeing with Ariadne to Naxos, Theseus abandons her there, never to return. In her later pieces, Leach has tried to recreate a "pre-Hellenic Ariadne," one less codified than the classic portrayal. Recently, in continuing her research, the composer came across this quote from historian Helmut Jaskolski [The Labyrinth, Symbol of Fear, Rebirth, and Liberation (translation by Michael H. Kohn)]: "The memory of Ariadne, the original lady of the labyrinth, has practically disappeared in the course of the history of European culture. What has survived in the male story of the Labyrinth is the clue that helped Theseus, the proverbial "Ariadne's thread." Sympathy for the Cretan princess has been expressed almost solely by composers. . . . At the end of the twentieth century, the moment has certainly come not only to lament Ariadne, but also to restore to her her ancient rights." As the composer writes: "How could I resist this quote, since I heartily agree with its conclusion?"

O Magna Vasti Creta is scored for women's chorus and string quartet. Underlying the entire piece are pedal tones, which provide an insistent underlying rhythmic pulse, as well as a reference pitch upon which the varying melodies superimpose themselves. The pedal tones are shared by both chorus and ensemble: when the chorus intones them, it is always to the word wanassa ("Queen").

The half-step-the closest that two notes can lie in the chromatic scale-is traditionally Western music's most powerful melodic motion and its strongest harmonic clash. The first section of O Magna Vasti Creta opens with such a half-step-D-flat and C-natural-intoned against each other. The C-natural is the stable pitch, by virtue of its unbroken presence, and the D-flat is repeatedly drawn down to it. For a while, carefully paced, that is all there is: the implication of melody, and the resolutely steadfast harmonic dissonance. Gradually, the texture thickens, as other notes are introduced. The mode created is an invented one, with C-natural as tonic, and an unpredictable zig-zag of scalar steps. Squeezed into one octave, the superimposition of the vocal lines creates a delicately pulsing cluster. Words are broken into rhythmically disjunct syllables, which the chorus slowly intones out-of-phase with one another.

Then the texture lightens, and to the words Ariadne agaklaya ("glorious Ariadne"), a melody is clearly stated for the first time, using the same notes as in the first section. The melody returns repeatedly, but at unpredictable intervals and with slightly varying phrase lengths, creating a mellifluous continuity. In responsorial dialogyue, osya potna thayawn ("Holiness, Holiness, queen of Heaven") answers with its own tune.

The shift in pedal tone from C-natural to G-natural introduces the text O magna vasti Creta ("Menacing, queenly Crete") in which the imitation and layering of voices reaches a climax. Here as well, the violins achieve the highest note in the piece. Different strands of text are intertwined, and the melodies are repeated sometimes a bar apart, sometimes a half-bar, creating another vision of steadfast, but gently unpredictable, prolongation. The piece comes to rest on the G-natural at the end, the change in pedal tones having created a long, underlying "Amen" cadence that is at once restful and suspensive, inviting further discourse.

In Call of the Dance, a solo voice is added to the chorus, now a capella. As the genesis in multi-tracking suggests, the chorus provides an underpinning, and receives only fleeting focus; on top of this, the soloist's soaring and expansive line traces itself out. All of the soloist's pitches are anticipated or reflected by the chorus, creating the impression that the chorus is in the "air" which the soloist breathes into her song.

The piece is framed by a similar texture at opening and end: The chorus members intone quick, oscillating fragments, while the soloist declaims in slower, more forceful statements. When this texture returns at the end, the soloist sings a completely new line, suggesting the text's "longing for a new song."

Windjammer is filled with Leach's trademark imitations and prolongations, although in a fabric reduced to the sparser three parts. From a rhythmically hesitant beginning, the piece develops a fluid sense of activity, punctuated by new rhythmic and melodic details. Here, with the scoring for the coloristically distinct winds, the passing of pitches from one instrument to another is particularly noticeable. The piece ends with a reflective nod back to its beginning.

In its distillation of Solage's "Très Gentil Cuer," Tricky Pan brings many of the Renaissance antecedents in Leach's music even more to the forefront: the freely shifting metric stresses; the emphasis on fifths and octaves; and the expressive use of "blue" notes, that is notes outside the harmony whose dissonance underlines a moment of textual poignancy. Formally, the piece is divided into two clear sections, separated by the piece's one long pause. The second section, which begins with the words "Quà vous amer" ("But to love"), presents most perceptibly a shift of harmony and new motivic details in the taped part. Taken as a whole, the piece is an extended, impassioned homage.

Monteverdi's Lamento d'Ariana is beautifully representative of that composer's immensely sensitive and flexible text-setting. Its close-fitting harmonies and aching dissonances are reflected in Ariadne's Lament, which isolates fragments from the Monteverdi and elaborates upon them. The piece opens with a long, densely textured, rhythmically continuous passage, which then leads to more isolated solo statements. Here, Leach's meditation on Monteverdi's gorgeous opening melody, Lasciatemi morire ("No longer let me wait"), is especially strong. A rhythmically more active passage follows, before the piece relaxes into a subdued close.

In Song of Sorrows,

the strength of the tonality is mediated by disquieting shifts between

major and minor tonalities. Though Leach usually declines explicit text-painting,

here there are some suggestive moments: for instance, at the word Misera

("Misery"), one strongly affirmed chord is suddenly supplanted by a distantly

related one. Near the end of the piece, to the words Invan piangendo ("In

vain my weeping"), the vocal line edges upwards along a nearly chromatic

scale, illustrating, with its sense of roving, unsettled focus, Ariadne's

hopelessness and insecurity.

-- Anthony K. Brandt